History of Fayette County

Fayette County's geographic location and the wealth of its natural resources have combined to produce two dominant periods of its history influences are still felt today- transportation via road and river, and the coal and coke era.

Parallel with both have been agriculture and commerce, and the opportunities inherent in the scenic beauties of the county, especially in the mountain area.

In the mid-18th century rivers were the only easily accessible means of transportation, and the French took the river routes down from Canada. The British struggled westward from the coast, over the mountains and toward the inevitable collision.

The one feasible land route from Virginia to the strategic point of the Forks of the Ohio (the future site of Pittsburgh) ran through the wilderness of what would become Fayette County. Early Indian traders, land agents and explorers blazed the way-Christopher Gist at Mount Braddock, William Stewart at Connellsville, Wendell Brown and his sons in Georges Township.

On their heels, in 1754 came George Washington leading his Virginians to reinforce an earlier contingent sent to build a fort at the Forks of the Ohio, heading first for Redstone Old Fort (Brownsville), where a storehouse had been built. His expedition ended in defeat by the French and Indians at Fort Necessity. The following year, the British regular, General Edward Braddock, improved Washington's path as he marched toward another and greater disaster near Pittsburgh.

Parallel with both have been agriculture and commerce, and the opportunities inherent in the scenic beauties of the county, especially in the mountain area.

In the mid-18th century rivers were the only easily accessible means of transportation, and the French took the river routes down from Canada. The British struggled westward from the coast, over the mountains and toward the inevitable collision.

The one feasible land route from Virginia to the strategic point of the Forks of the Ohio (the future site of Pittsburgh) ran through the wilderness of what would become Fayette County. Early Indian traders, land agents and explorers blazed the way-Christopher Gist at Mount Braddock, William Stewart at Connellsville, Wendell Brown and his sons in Georges Township.

On their heels, in 1754 came George Washington leading his Virginians to reinforce an earlier contingent sent to build a fort at the Forks of the Ohio, heading first for Redstone Old Fort (Brownsville), where a storehouse had been built. His expedition ended in defeat by the French and Indians at Fort Necessity. The following year, the British regular, General Edward Braddock, improved Washington's path as he marched toward another and greater disaster near Pittsburgh.

After the British finally won the French and Indian War, after capturing Fort Duquesne and renaming it Fort Pitt in 1758, the settlers came back over the mountains and set up subsistence farming. The Braddock Road from Cumberland wound northward from Fort Necessity down the mountain to the Gist Plantation and on to the north through Connellsville. A connector was needed to the west and Col. James Burd supplied just that in 1759, with the help of the Indian chief Nemacolin, by the laying out a road from Gist's to Brownsville (where he built Fort Burd). These routes provided the basic network which the National Road would follow.

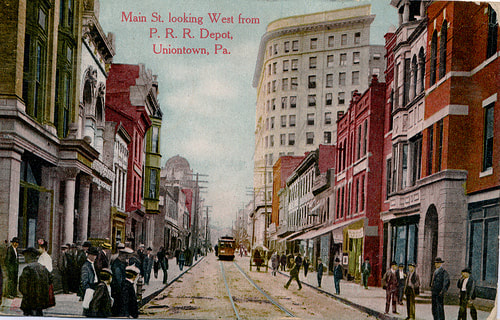

Communities grew up at natural geographical centers, sparked by mill owner Henry Beeson in Uniontown, Col. William Crawford and Zachariah Connell at Connellsville, John Brown and the trader Jacob Bowman at Brownsville, John Mason at Masontown.

In the 1770s the territory that would become Fayette County was claimed by both Pennsylvania and Virginia, with the spectacle of rival county governments existing at the same time and fighting each other. The dispute was settled in 1780 when the Mason-and-Dixon Line was extended to the original limit of Penn's land grant, giving Virginia frontage on the Ohio River.

Times were hard on the frontier before and during the Revolution, when Fayette Countains had to fight off Indian Attacks, building forts for protection. On one punitive expedition into Ohio 1782, Col. William Crawford of Connellsville was captured, toured and slain.

Fayette County was created out of the southern part of Westmoreland Country in September 1783 and named for the young French hero of the Revolution, the Marquis de Lafayette. Uniontown, which had been founded on July 4 1776, was chosen as the county seat.

The frontier farmers staged the Whiskey Rebellion in 1791-94, protesting a federal excise tax on whiskey with attacks on the tax collector. The insurrection ended in surrender to a federal army, and went down in history as having provided the first real test of the new U.S. Constitution.

At about the same time, the first industrialization appeared with the iron furnaces in the mountains, taking advantage of deposits of iron ore and abundant wood for charcoal.

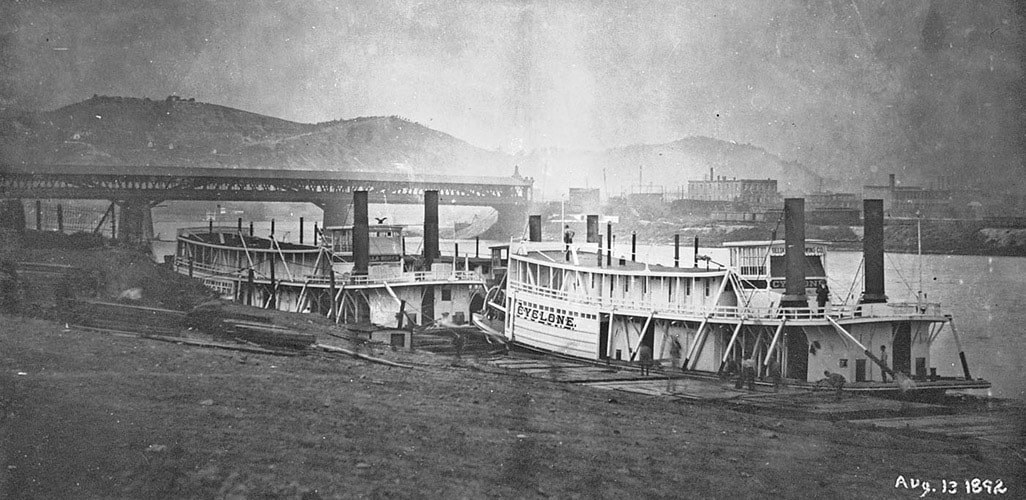

Strategically located on the Monongahela River, Brownsville quickly became a center for construction and dispatch of flatboats, keelboats and later the new steamboats.

In the 1770s the territory that would become Fayette County was claimed by both Pennsylvania and Virginia, with the spectacle of rival county governments existing at the same time and fighting each other. The dispute was settled in 1780 when the Mason-and-Dixon Line was extended to the original limit of Penn's land grant, giving Virginia frontage on the Ohio River.

Times were hard on the frontier before and during the Revolution, when Fayette Countains had to fight off Indian Attacks, building forts for protection. On one punitive expedition into Ohio 1782, Col. William Crawford of Connellsville was captured, toured and slain.

Fayette County was created out of the southern part of Westmoreland Country in September 1783 and named for the young French hero of the Revolution, the Marquis de Lafayette. Uniontown, which had been founded on July 4 1776, was chosen as the county seat.

The frontier farmers staged the Whiskey Rebellion in 1791-94, protesting a federal excise tax on whiskey with attacks on the tax collector. The insurrection ended in surrender to a federal army, and went down in history as having provided the first real test of the new U.S. Constitution.

At about the same time, the first industrialization appeared with the iron furnaces in the mountains, taking advantage of deposits of iron ore and abundant wood for charcoal.

Strategically located on the Monongahela River, Brownsville quickly became a center for construction and dispatch of flatboats, keelboats and later the new steamboats.

The National Road was built by the federal government from Cumberland to Wheeling in 1811-18, with its route through Uniontown, Brownsville and Washington assured by the early Fayette County politician and statesman Albert Gallatin. It brought prosperity, creating an entire culture of its own, with freight-laden Conestoga wagons, stagecoaches, “movers” heading west, and huge herds and flocks of livestock. The road opened up the Northwest Territory, reaching vast areas not accessible to rivers. The National Road (it became a toll road, or Pike, after the states took it over in 1835) was the lifeline of a growing nation, and continued as such until the railroad reached Wheeling in 1852.

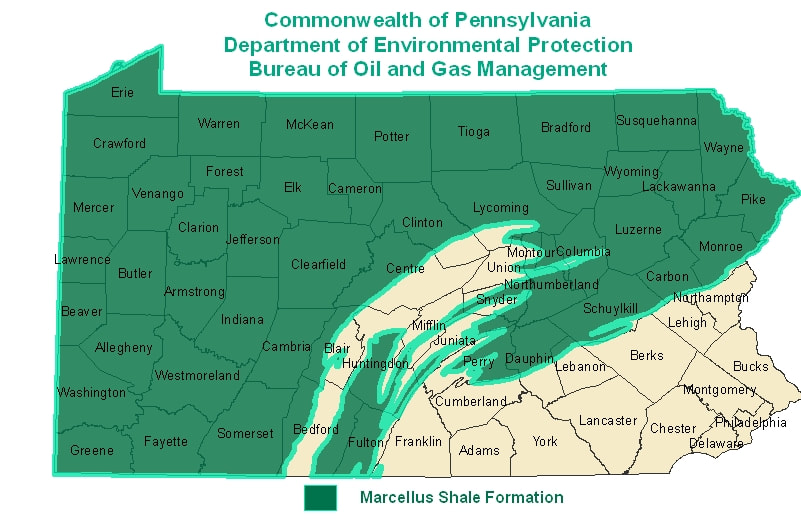

The presence of bituminous coal had been recognized early, and small mines were opened, but the soft coal could not withstand the rough handling of primitive transportation for long distances. The breakthrough came with the discovery of the coke-making process, and Fayette County coke was one of the essential ingredients upon which the Pittsburgh steel empire was built.

The pre-eminence of Fayette County and the adjoining section of southern Westmoreland County in the coal and coke industry was based on Connellsville Coking Coal, the best metallurgical coal ever discovered. The first great mines and cokeyards sprang up in the 1870s and 1880s in the narrow section from Latrobe south through Scottdale, Connellsville and Uniontown to the Fairchance-Smithfield area.

Later the coal fields expanded into the “Klondike” area, from Uniontown west to the Monongahela River. New towns appeared seemingly overnight to accommodate miners, many of them immigrants from Europe, and the county’s population exploded. Fortunes were made in coal land dealing, notably that of Uniontown’s J.V. Thompson.

The coal and coke boom continued through ups and downs until about 1950s, by which time almost all of the large Fayette County mines were worked out. The beehive ovens, which had reached a total of 44,000 at their height (28,000 in Fayette County, 16,000 in neighboring southern Westmoreland), disappeared as the more efficient by-product ovens took over.

At least 150 coal “patches” (housing communities built and owned by the coal companies) have been identified in Fayette County, of whom more than 50 remain as sizable communities, with the houses now individually owned. There were more than 300 mines.

Fayette County’s population dropped from a high-water mark of 200,000 in 1940 to an estimated 150,000 today.

Fayette County possesses some diversified industry, in glass, water meters, steel fabrication and other enterprises. Some strip mining remains, and miners commute to other counties. The county retains its position as an important wholesale and retail trading center, still a crossroads area despite substandard highways. The future hope for industrial development, enhancement of tourism and commercial prosperity is wrapped up once more in better road and river transportation.

The presence of bituminous coal had been recognized early, and small mines were opened, but the soft coal could not withstand the rough handling of primitive transportation for long distances. The breakthrough came with the discovery of the coke-making process, and Fayette County coke was one of the essential ingredients upon which the Pittsburgh steel empire was built.

The pre-eminence of Fayette County and the adjoining section of southern Westmoreland County in the coal and coke industry was based on Connellsville Coking Coal, the best metallurgical coal ever discovered. The first great mines and cokeyards sprang up in the 1870s and 1880s in the narrow section from Latrobe south through Scottdale, Connellsville and Uniontown to the Fairchance-Smithfield area.

Later the coal fields expanded into the “Klondike” area, from Uniontown west to the Monongahela River. New towns appeared seemingly overnight to accommodate miners, many of them immigrants from Europe, and the county’s population exploded. Fortunes were made in coal land dealing, notably that of Uniontown’s J.V. Thompson.

The coal and coke boom continued through ups and downs until about 1950s, by which time almost all of the large Fayette County mines were worked out. The beehive ovens, which had reached a total of 44,000 at their height (28,000 in Fayette County, 16,000 in neighboring southern Westmoreland), disappeared as the more efficient by-product ovens took over.

At least 150 coal “patches” (housing communities built and owned by the coal companies) have been identified in Fayette County, of whom more than 50 remain as sizable communities, with the houses now individually owned. There were more than 300 mines.

Fayette County’s population dropped from a high-water mark of 200,000 in 1940 to an estimated 150,000 today.

Fayette County possesses some diversified industry, in glass, water meters, steel fabrication and other enterprises. Some strip mining remains, and miners commute to other counties. The county retains its position as an important wholesale and retail trading center, still a crossroads area despite substandard highways. The future hope for industrial development, enhancement of tourism and commercial prosperity is wrapped up once more in better road and river transportation.

(condensed from 1983 article for Pennsylvania Heritage Magazine)

Revised 6-22-92 By Walter J. Storey, Jr.

Revised 6-22-92 By Walter J. Storey, Jr.

|

|

|